Back in February we announced that Angela Blažanović was the chosen artist for our 2020 Capture Public Art Project! A big thank you, once again, to everyone who submitted to the open call. Angela’s images were installed on the facade of the King Edward Canada Line Train Station, here in Vancouver, as part of Capture 2020. You can see her beautiful work in the image above — photo by Jeffro Halliday.

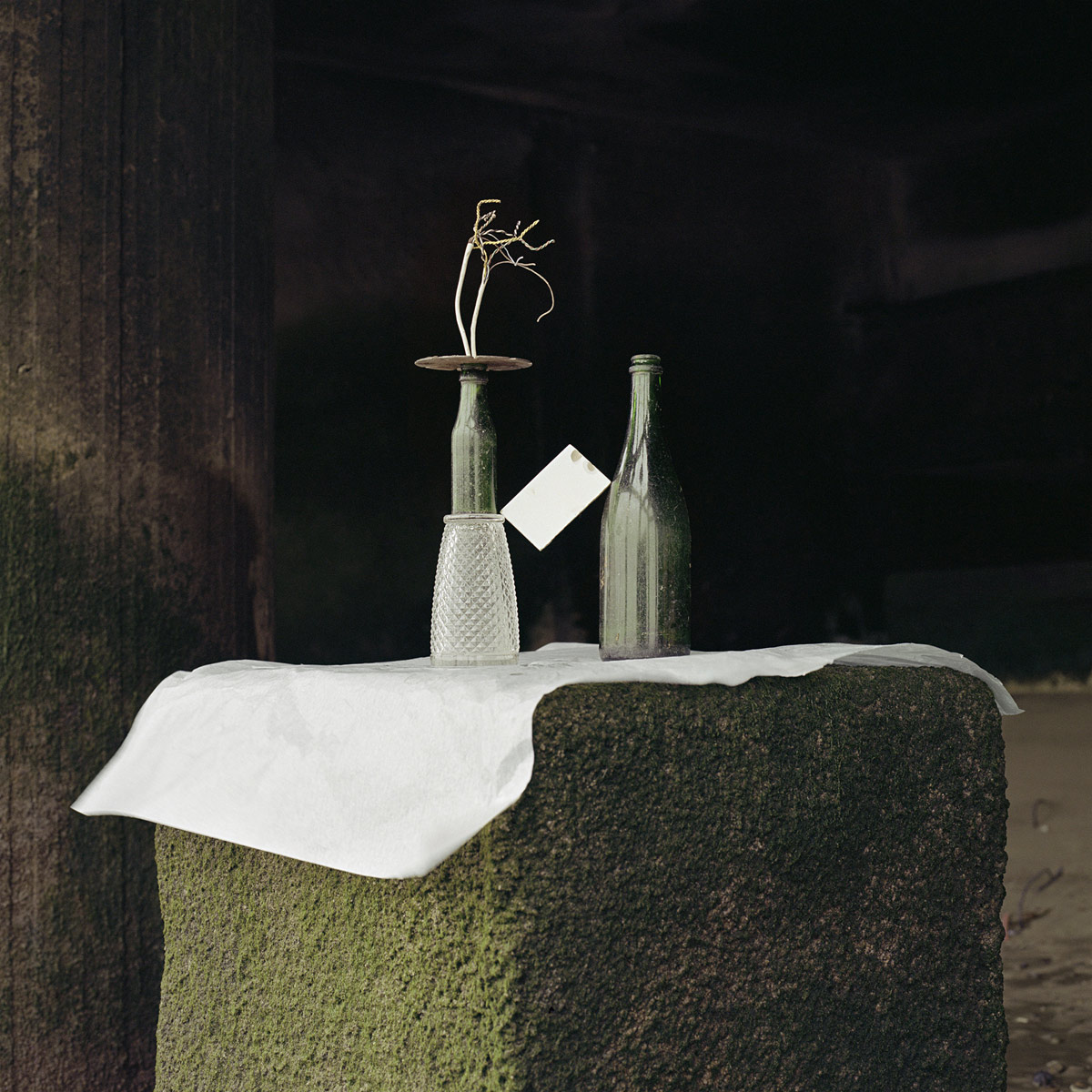

The three images come from Angela Blažanović’s series “Fragments of a River”, in which she arranged and photographed discarded objects retrieved from the banks of the river Thames in London, England. I had the opportunity to ask Angela some questions which provide some more context for the work.

Jeff Hamada: How’s London these days? What’s the last month or so been like for you?

Angela Blazanovic: I actually decided to come to Germany and stay with my family for the time being. I left around mid-March so I didn’t experience the impact of the full lockdown in the city myself. But I stay in touch with friends who are isolating in London and even from afar the situation feels quite eerie. I guess it’s very strange to see such a busy city change so much over the course of a few days really. The first few weeks the scenes in supermarkets were just worrying, but the situation seems to have calmed down a bit. I am just happy that everyone close to me is staying safe.

The last month, as for everyone else has been an adjustment for me, but it was nice to be able to spend it with my family. We live in the countryside close to a forest, so quarantine life here feels much easier and calmer than in London. I have spent the time catching up on some books and research. I also try to make use of the free online resources at the moment — many artists and organisations are sharing talks or workshops which are an amazing way to stay informed and motivated. My cameras have also just arrived from the UK so hopefully I can start some new work soon.

JH: Do you come from a creative family?

AB: I think my mother would have loved to do something creative. I know she used to draw and photograph when she was younger, but she pursued a different route. For this reason, I assume she always encouraged my sister and I to do whatever we wanted. We both became interested in arts and we used to paint and draw a lot growing up.

My sister ended up studying experimental film. Not far from photography at all yet different. Often it is great to hear her advice on my projects as a filmmaker; it helps to view my work from a new perspective. Does that make us a creative family? I’m not sure.

JH: What was the first image you created that you were proud of?

AB: This is a very difficult question; I have actually never thought about this before.

It must have been a photograph I took during a photography summer school in 2015, I believe. I used to take pictures as a teenager, but they were mostly ‘pretty’ images. During the short course I learned more about the conceptual thinking behind an image and it made me understand photography as an art form for the first time. It was also my first time to shoot on film. I completed a very small series of images in the course of two weeks which I felt, and still feel, proud of. The photographs were purposely shot out of focus — the scenes were blurred, and individuals became fleeting silhouettes. The images correspond to the deceptive nature of memories and dreams. I remember one photograph in particular. It showed an entrance and two figures seemed to be rushing through. It somehow reminded me of a hospital environment and evoked an anxious feeling. In my display, the same image reoccurred multiple times, similar to a nightmarish memory that has imprinted itself into one’s subconscious.

I was fascinated how these images opened up to an entirely different context. It was a very new approach to photography for me and the first time I was trying to achieve something beyond a ‘pretty’ image.

JH: Let’s talk about your series, “Fragments of a River”, did you set out to make a body of work with an environmental message or was it something that came about more organically?

AB: Actually, it was something that just happened as I was working through the project. My initial inspiration for this series derived from my first visit to the river shore of the Thames. I was instantly fascinated with the idea that one could walk on ground which hours later would be filled with water. Interested in the duality of the river, which changes endlessly between calm sanctuary and dangerous stream, I set out to produce work which would reveal new ways of looking at the river.

During this first visit I came across all these random objects; things people had either lost or thrown away. This litter had seemingly become part of the landscape itself. I felt a strong fascination for those objects and started imagining the stories that lay behind them. The project really developed from there; I started experimenting with ways of shooting the objects that would put them in a new context and make the viewer revaluate their existence.

And, although it was not my initial intent for the project, the theme of plastic pollution and environmentalism naturally came up very quickly. I started doing more research and learned about the Anthropocene, the theory that humans have introduced a new geological era on earth. I became interested in the idea that a landscape could speak of the humans it inhabits.

It made sense to let the project dictate the message, to research this current issue further and incorporate it in the work; and possibly even have a positive impact on it.

JH: The ephemeral aspect to the work is interesting. After building the sculptures and documenting them you chose to allow the objects to be swept back into the water, can you talk a bit about this decision?

AB: At some point during the project it simply felt natural to me to leave the compositions behind. It first started as a test, I wanted to see what of my creations would remain and if I could retreat the paper that I had brought into the scene in order to incorporate it into the work. Unfortunately, nothing was left the next morning. I tried it a couple of times, even putting heavier objects and rocks on top. But again, nothing remained.

Seeing the empty pillar in the morning made me rethink my whole process and the sculptures that I was creating. My intervention within the space could only ever be temporary. At low tide the river offers a beautifully calm landscape, a sanctuary. But within hours the water rises transforms it into a dangerous, destructive stream. By leaving the objects behind I am allowing the river to become an active participant in the work. Whatever I extract from the river and create, the river washes away. It is an endless cycle of creation and destruction — the river holds potential for both.

AB: The temporary nature of the compositions is central to the work. I try to translate this fragility into the sculptures themselves. All objects are carefully arranged on top of each other. Although the compositions are captured in a moment of perfect balance, the anticipated collapse is evident within the photograph and speaks to the short-lived nature of the sculptures as well as the ambiguity of the river.

By the way it might be worth mentioning that although I leave the compositions behind, I do collect a lot more material than what I end up using. Usually I collect around two bags which I take with me and try to recycle where possible.

JH: Had you ever considered exploring this project without the aspect of the lens?

AB: I don’t think I ever considered not using a camera at all. I certainly tried to experiment with ideas that go beyond the photographic image. And different disciplines play into the work: sculpture, performance, site-specific installation, but I always have the photograph as last outcome in mind.

I could collect the objects and create sculptures in a different setting, but for me it would dilute the impact of the work. The sculptures have to be created where the objects have been extracted from the river shore itself. Because of the tide the installation can only ever be temporary, and photography has allowed me to document these short-lived compositions within the location.

JH: I read somewhere that you felt like you failed a lot in the process of creating the images. What were some of the things you tried that didn’t work?

AB: I like to experiment with a lot of different approaches to shooting a project. Failing is part of that process. Unfortunately, at times it can be frustrating. It can feel like you are not making the expected progress, but at the same time it is important to learn to value mistakes and accidents; it ultimately forces you to revaluate your approach.

For example, I started this project using a digital camera. I thought it would be more efficient to figure out how to shoot this project before I would take the final images on film. But down at the river shore I only have limited time to shoot and with a rising tide I started to rush. I ended up shooting hundreds of images that just weren’t that strong. I tried different ways of shooting along the shore, but it just didn’t come together. I decided to collect the objects and bring them into the studio, thinking it would give me more time to create stronger compositions as well as control the lighting. I ended up with three very strong studio still lives, but the photographs had lost the connection to the river. The pieces of litter could have come from anywhere really. I tried to experiment sequencing the still lives with waterscapes, but in the end the objects felt too removed from the context of the river.

At this point I decided to go back to the river shore and shoot on an analogue medium format camera. And it instantly worked. Even with a rising tide behind me the analogue process forced me to slow down and make more considered decisions about my constructions, resulting in stronger images.

I also tried shooting on 5×4 in the studio. But I must have made a mistake during the developing of the negatives. Both images showed a big light half circle of light coming in. I was incredibly upset and frustrated over it, as setting up the final still life had taken me around 5-6 hours. Nevertheless, after I had the time to step back from it, I realised that the bright half circle actually added to the composition of the image. I still like the photograph although I obviously did not end up using it as I returned to shooting along the river.

Even the reference to 17th century still life painting was a lucky accident really. It just happened that I tried shooting on this concrete pillar that you can see in the final images. At certain times during the day the light falls perfectly onto the pillar keeping the background in the shadow. But it wasn’t until afterwards when I was presenting my contact sheets that someone pointed out the similarity to Vanitas painting. It was only at this point, that I started researching Vanitas paintings in order to consciously enhance the reference in the images. A good example of a lucky accident, I guess.

JH: How has your approach to creating art changed over the past couple years?

AB: I would say I have become more open minded about what photography is and can be. While earlier on I was more concerned about documenting a subject matter, I have become more and more interested in the artistic process itself. I have started to experiment with other disciplines and bringing them into my work. I am continuously trying new approaches to photography, making mistakes and learning new ways of thinking.

JH: What’s one piece of advice someone has given you that you’ve found to be true?

AB: One piece of advice I will probably always remember is something my old course leader Mick Williamson used to tell us over and over again: ‘Shoot more!’. He shoots multiple rolls of film every day on a small half frame camera and has created an incredibly large archive of images documenting moments of his everyday life. He has learned to really feel the photograph, rarely even looking through the viewfinder.

Although I will probably never get to the point of shooting multiple rolls a day, I find there is something very important in this simple advice. Whenever I would feel lost or stuck with my projects Mick would say ‘Shoot more!’, and it helped. It is so much harder to evaluate something that doesn’t exist. While if you go out and shoot anything at all, you have something to think about and work from. It doesn’t matter what stage you are at with a project or if you do not even have a concept at all. You can only make progress if you actually try things out and produce images. There are times when I do not take pictures for weeks or even months, then I start hearing Mick in my ear and pick up a camera.

JH: What’s next for you?

AB: I am incredibly proud to see the work up at the King Edward Station. One of the reasons why I submitted to this Open Call was because I really feel that the work lends itself to engage with people in a public space. It confronts us with the urgent matter of plastic pollution that is present in our own environment. I would love to see the series in more public spaces, possibly billboards across different cities, but firstly in London itself.

It is also time that I dedicate myself to a new project. I have been pondering over different ideas for a while now and am eager to start shooting again.

Images: Angela Blažanović, from series ‘Fragments of a River’, 2019

Angela Blažanović on Instagram

2025 Art & Photo Book Award

Wanna turn your art or photos into a book or a zine? Here’s your chance, we’re picking 9 people!

Learn moreJoin our Secret Email Club

Our weekly newsletter filled with interesting links, open call announcements, and a whole lot of stuff that we don’t post on Booooooom! You might like it!

Sign UpRelated Articles