Continuing our partnership with STORYHIVE — a platform which supports BC and Alberta based creators — we had the opportunity to interview director Hayley Gray whose latest film, Hayashi Studio, explores the often overlooked history of Japanese Canadians through the archives of photographer Senjiro Hayashi.

What kinds of things were you into as a kid growing up in Kingston, Ontario?

I loved stories. I’d walk around with my girlfriends for hours making up stories. I auditioned for everything theatre, my first role was a pinball machine. My parents put me in sports but I wasn’t great at competition or coordination, so that didn’t stick. In high school, I was in academic clubs and was overly enthusiastic about school. Hand constantly up — Hermione style. No social skills. I was counting down the hours until I could go back to the theatre. I felt seen there in a way I didn’t anywhere else.

But to reflect back on Hayashi Studio, what I learned growing up in Kingston was primarily white settler history. I learned about founding fathers and suffragettes, forts, capitals and conflicts with the Americans and the French. I didn’t learn anything about the Japanese, Indian, Chinese or African communities in North America, and any Indigenous references implied that their place was in our distant past. There was a clear dominate narrative and everyone else was a bit player.

What were your first experiences in front of, and behind, a camera?

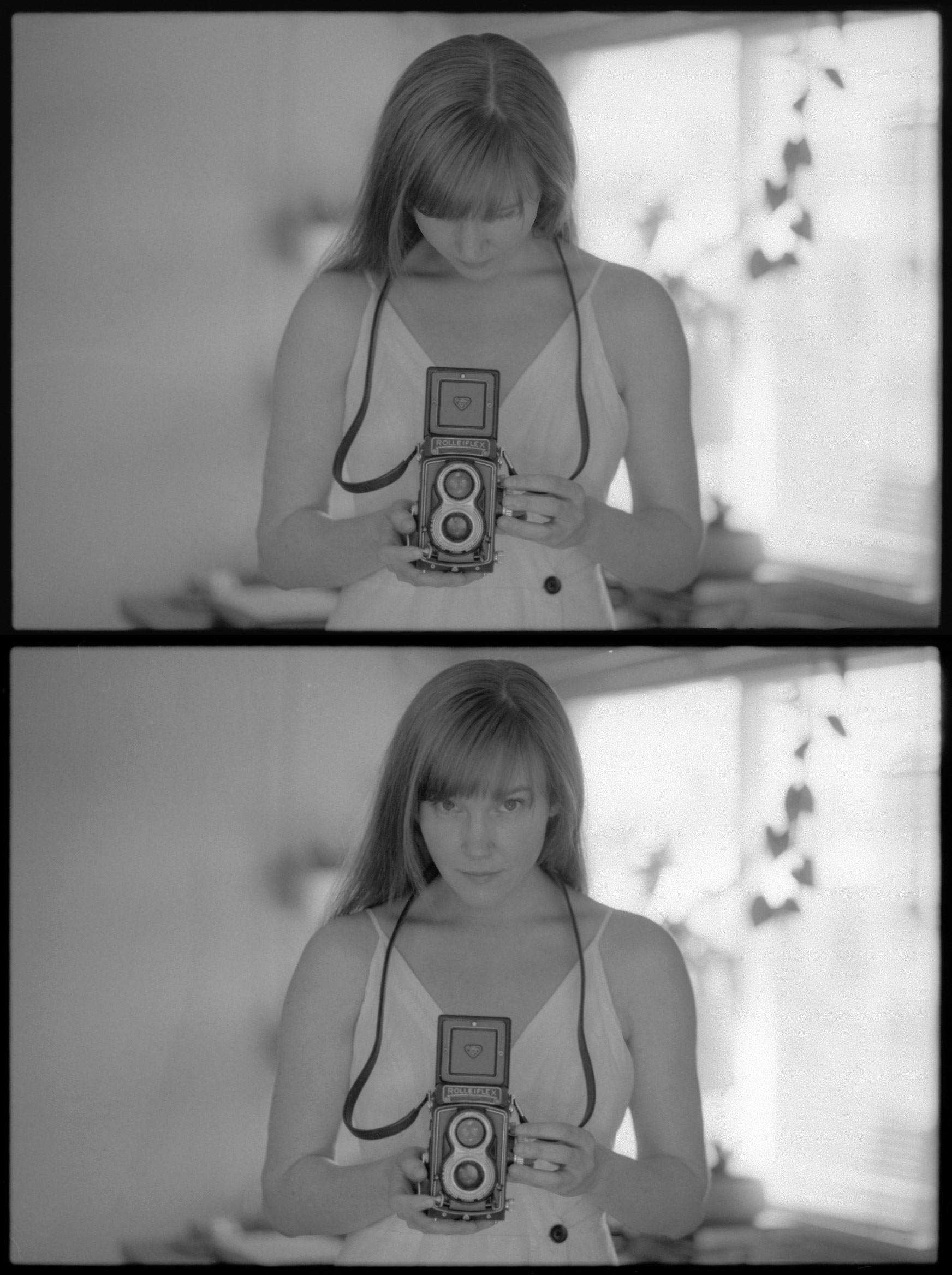

I took a photography class in high school, experimenting in the blackroom with photos and collaging. It was such a delicate thing and I was such a clumsy kid. I was sure each time I had to transfer the film over that I would ruin it, but somehow it all came out okay. I still have those, I think, photos of classmates and bleak Ontario winters in black and white.

I put all of that away for a long time. After high school I spent my undergrad studying psychology and political science. I ran the university women’s centre, a community-supported agriculture initiative and tried to find a more traditional career path. But when I got into a masters program and the future was looking me right in the face, I couldn’t do it. I knew I’d regret not pursuing film. I gave up my life on the East Coast, got on a plane and went to crash on the couch of the one friend in Vancouver in order to go to film school.

I started as a performer but quickly realized that I wanted to be more involved. I felt like I was sitting in a trailer while the crew was bonding and creating something together, only showing up for the final moments. And, like many, I had stories I wanted to tell. I made a connection with my former writing professor and worked with him to develop my first feature script. After that, I took to writing and eventually directing.

I worked as a production coordinator, then production manager. I thought it was a good way to learn the dynamics of film. You hear about everyone’s complaints, revel in their successes. You read tone bibles and scripts, you sit in on meetings examining all the different facets of the creative process, you problem-solve huge complicated scenes. I think, for me, it was the best education I could ask for. It allowed me to take what I knew about performance and story and shift into directing.

The first thing I directed was a short film called “Macchiato To Go” which featured my good friend Amanda, a barista who refused to serve macchiatos to-go. It wasn’t perfect but it was sweet and personal, after watching so many directors work, I finally got to tell a story.

How has your approach to filmmaking changed over the years?

When I first started out in film, it was about the words, I was a performer first and connected most deeply to pulling the words off the page. It really took some time to understand how to tell a visual story. I’m getting better at it and enjoying the process more and more.

I’m continuously working to better speak to my own experience while trying my best to hold space for others. I really struggled with Hayashi Studio to figure out the balance between my experience and our subject’s perspective. I wanted to step all the way out, but I knew it needed to be honest about my point of view, I don’t believe in objective observers.

At the same time, I struggled with whether this was my story to tell or not. This wasn’t my community. Then I met Grace. She invited me to her apartment and we spent hours drinking green tea and talking about chauvinism, racism and colonialism. As I was getting ready to go, she told me that she wanted the curation of the photos to be the beginning of the conversation and that she wanted me to continue it. I took it as an invitation, I ran with it.

What’s stayed the same?

I’m always searching to explore moments of great feeling. Moments of tenderness, moments of revolt. I think especially when you look at Grace and Flo’s storylines you see women who have been in revolt their whole lives and are much the better for it, gives me faith, gives me role models.

I’m obsessed with finding the universal in the specific. What I love about Hayashi Studio is it speaks to something that is both a radical reexamination and a simple story that everyone can get behind: a desire to understand a history most haven’t had the chance to consider before.

Japanese Canadian history isn’t talked about a lot, what made you want to make your film, Hayashi Studio, and why specifically investigate the time just before the internment of Japanese Canadian families?

When we showed the finished film in Cumberland one audience member came up to me after the screening and told me that she felt like I had uncovered a cultural genocide. But the reality is BIPOC communities have been speaking to this cultural genocide for decades. For me, his photos contextualized this in a new way. I think (hope) the film’s been able to do that for others.

It makes me mad that throughout North America what we know (and what we teach) with regards to racialized communities is the worst moments in their past, we don’t learn about the successes, we learn about the setbacks and the atrocities. Japanese North American’s have been here for a hundred and fifty years, there is at least sixty years of Japanese-Canadian history before 1942, longer if you look in the US. How do we learn to care about communities when we’re only taught about the moment they lost everything? When we learn that they are footnotes in another story?

What do Senjiro Hayashi’s photos mean to you?

When I first saw Hayashi’s photos, I can’t explain how deeply they struck me. Many times, Laura (the Anthropologist we worked with) told me, “there were so many other people here, we should know more than just white colonial history.” And in theory, I understood that, but when I saw Hayashi’s photos the disparity became so profound. I had never seen photos of a diverse community, taken by someone within that community from that time. On top of that, they were so well composed, so precise, so beautiful.

What cut deep with Hayashi’s photos is knowing that there were hundreds of diverse communities throughout BC’s history that didn’t have a photographer and because of that, we would never get to know them like this.

The photos are a constant reminder that everyone’s history is important. When I go out to meet knowledge keepers on these research trips, so often I hear, “Why do you care? Or doesn’t matter anymore.” The interview I found from Mickey Hayashi (Senjiro’s son) that allowed me to find the Hayashi family finishes with: “I don’t know what you are going to do with it.” It being the interview. There’s often this feeling that their stories aren’t important, and it’s never true. In the film there is a particular photo that we reference, it is that of Ginger Goodwin’s Funeral procession. Without Ken Hayashi’s photo the procession, would we be able to comprehend the level of solidarity that led to the first general strike in Canada?

I think what I love most though are the simple moments in people’s lives that we would never get to see otherwise, [the photo above] has always been one of my favourite photos, I know nothing about this family of women, but you see the shyness of one, the obstinance of the other, the shine on their shoes and the mix of Chinese and European clothes. It’s such a reflection.

Tell us about the chair.

I think one of the first things I knew about Hayashi Studio is I didn’t want it to be a vérité film. Hayashi’s photos had such regality and style, even the most ad hoc photos were so beautifully composed. And I wanted the film to feel like his photos.

A few years ago I went to TIFF for the first time and watched Mina Shum’s documentary Ninth Floor. There, I had a chance to hear her speak about it. Surveillance is at the centre of the story and Mina shot from the vantage point of a security camera, using long shots and overheads. I thought about that as I started to think about how I wanted to showcase Cumberland, our subject and Hayashi’s photos. What could I do visually to pay homage to his work and his subjects?

That’s when I started to collaborate with our production designer Caitlin Byrnes to find a few pieces to reflect Hayashi’s studio, the Roman backdrop, the blue china pot with its little fern and of course the Morris Chair. Caitlin searched high and low to find a chair that would match and we reupholstered it to get it as close as we could to the original.

What were some of the biggest challenges of making the film?

This was my first official attempt at documentary work. I’d made shorts for Laura before, documenting her research and digitization through Populous Map, but I never made anything of this magnitude. I was so worried about story. I wrote out my story so many times in so many ways and reverse engineered my questions and viz list from there, praying I didn’t miss anything and praying I left enough room for magic. My producer/editor/partner Elad reminded me over and over again that editors never have enough B Roll to work with, so my camera team (Kaayla Whachell and Brock Newman) and I would be out just before sunrise and until sunset to shoot everything and anything that might help tell the story. I could not think of better people to spend dawns and dusks with.

What was the most rewarding moment for you?

I think the moments between Doug and Flo were some of the most rewarding in the film. When she took him to the former grounds of his grandparent’s school, where his father grew up. When she brought him a book which spoke to his grandparents being the most highly regarded Japanese Language teachers in the country. Those were so precious. I was also anxious to know whether or not the Hayashi’s would like and appreciate the film. When I sent the finished film to them I got an email back from Dennis Hayashi (Brent’s dad). He told me he wished his parents could have seen it. That meant everything to me.

Did your research spark any interest in either following this story further or perhaps investigating other stories which have been overlooked or forgotten?

Oh yes, the truth is, it’s still unfolding. Work like this is never done and there’s always another take, another perspective, another story.

Elad and I are working with the National Film Board on a longer form project that examines other overlooked aspects of British Columbia’s past. And I’m investigating more and more racialized and women photographers throughout BC examining their impact on our history. Perspective really changes things in such a profound way.

Do you feel like filmmaking is what you were born to do?

Yes. I’ve been many things and none have fit so well. I love making movies, and I love that you can reach people in such a personal way through them.

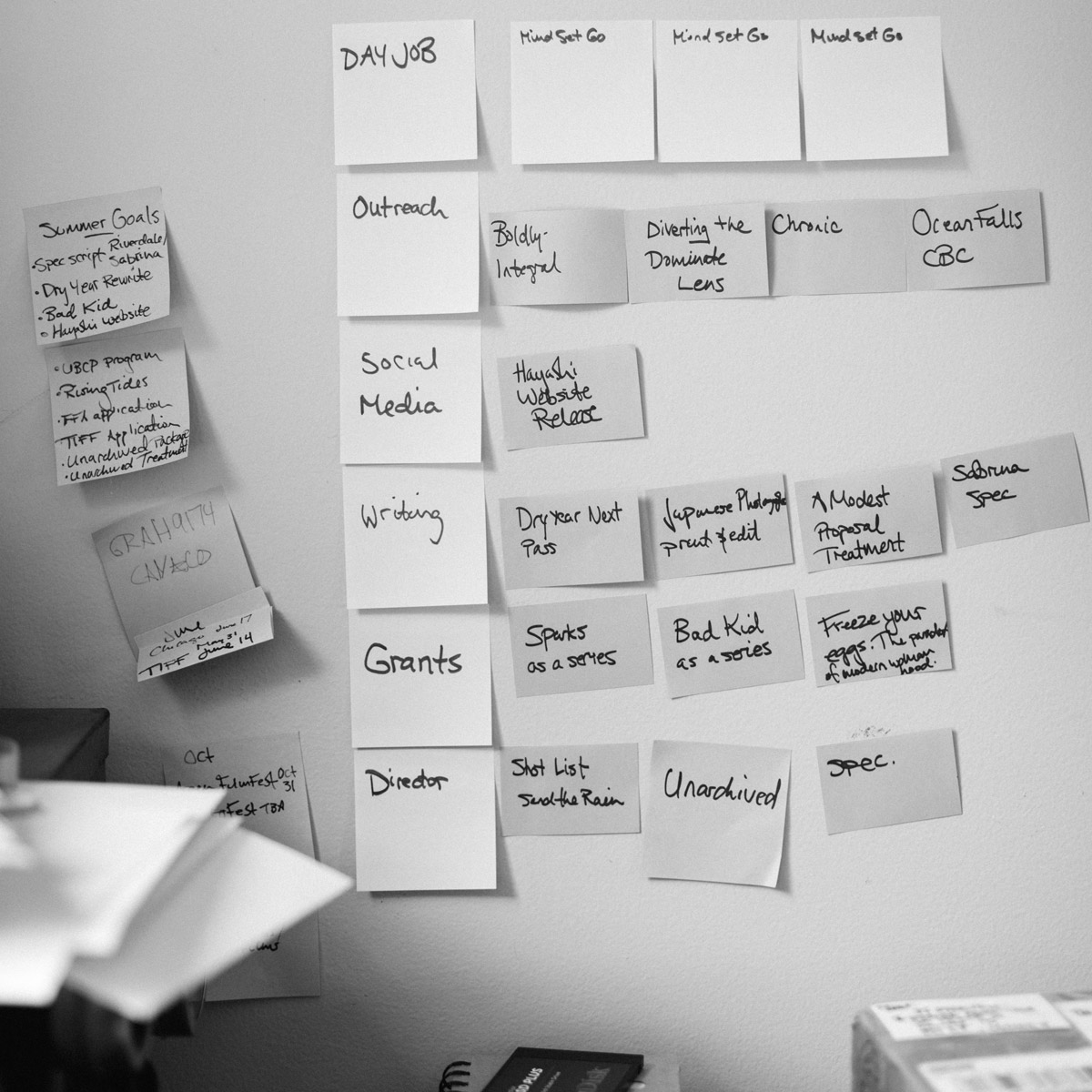

What’s one thing you’d like to accomplish in the next year?

I want to make our next documentary everything it ought to be, and do justice to the untold stories in BC. On the East Coast, I was often told that Vancouver was a young city and that there wasn’t a rich history in British Columbia, boy were they wrong. I’ve never found myself moved by history than the way I am out here.

What about something you’d like to accomplish in your lifetime?

Oh god, I really just want to direct movies that give people the feels and share some universal experiences. If I get to do that with my life I’ll consider it well lived. Oh and a Vimeo Staff Pick, definitely on the bucket list.

Join our Secret Email Club

Our weekly newsletter filled with interesting links, open call announcements, and a whole lot of stuff that we don’t post on Booooooom! You might like it!

Sign UpRelated Articles