An ambitious collaborative project by Birmingham-based photographers Cary Norton and Jared Ragland (aka Gusdugger). Specializing in 19th century wet-plate collodion tintype, the photography duo document the people and landscapes of Alabama using large format vintage cameras, hand-crafted chemistry and a mobile darkroom.

Started in 2016, “Where You Come From is Gone” seeks to make visible the historical erasure that occurred in the American South between Hernando DeSoto’s first exploitation of native peoples in the 16th century and Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act 300 years later.

Journeying more than 1,500 miles and across 20 counties to visit indigenous sites bereft of any obvious vestiges of Native American cultures, Ragland and Norton deliberately document absence. The resulting collection of wet-plate collodion landscapes attempt to put viewers in touch with history, helping us not only to imagine what was but to consider how best to honour what has been lost.

See more images from the series along with Gusdugger’s detailed descriptions below.

Bessemer Mounds, Jefferson County, Alabama, 2017

The Bessemer Mounds were first occupied during the Late Woodland Period between 800-1000AD. The mounds were leveled sometime in the 1900’s; VisionLand, a defunct theme park, and a water sewage plant are now located on the site.

Coosa River, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017

Near this point in the Coosa River, Pathkiller, the last king and full-blooded hereditary chief of the Cherokee, operated a ferry during the 19th century. After Pathkiller became too old to operate the ferry he spent his final days on the banks of the river, watching the water and river boats pass by. He was buried on the bluffs overlooking the Coosa, his body laid to rest facing the river.

Near DeSoto Falls, DeKalb County, Alabama, 2017

In June 1570, a small scouting group from Hernando DeSoto’s army of conquistadors made their way up Lookout Mountain to what is today known as DeSoto Falls, where they camped for at least two days and searched the area for gold and precious stones.

Cahaba River, Dallas County, Alabama, 2017

For millennia people have been drawn to the land situated at the confluence of the Cahaba and Alabama rivers. It was first occupied by large populations of Paleoindians; then from 1000-1500 the Mississippian period brought agriculture and mound builders. A walled city with palisades greeted Spanish explorers before western disease killed thousands in the 16th and 17th centuries. The remaining native peoples coalesced into four tribal nations – Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek – but were wiped out and forced to move by greater influx of Europeans. By the 19th century the dirt from the ancient mounds at Cahawba was used to build railroad beds, and the town became the first, yet quickly failed, capital of Alabama. A few short years later buildings and homes were taken down brick by brick and used to build Selma, home to further injustice.

Garrett Cemetery, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017

Outside the gates of the Garrett Cemetery is the final resting place of Pathkiller, the last king and full-blooded hereditary chief of the Cherokee. During the American Revolution Pathkiller allied himself with the British and fought against American troops, but by 1813 had sided with Andrew Jackson’s militia in the Creek Wars. Just three years after Pathkiller’s death, Jackson forced the Cherokee from their ancestral homelands.

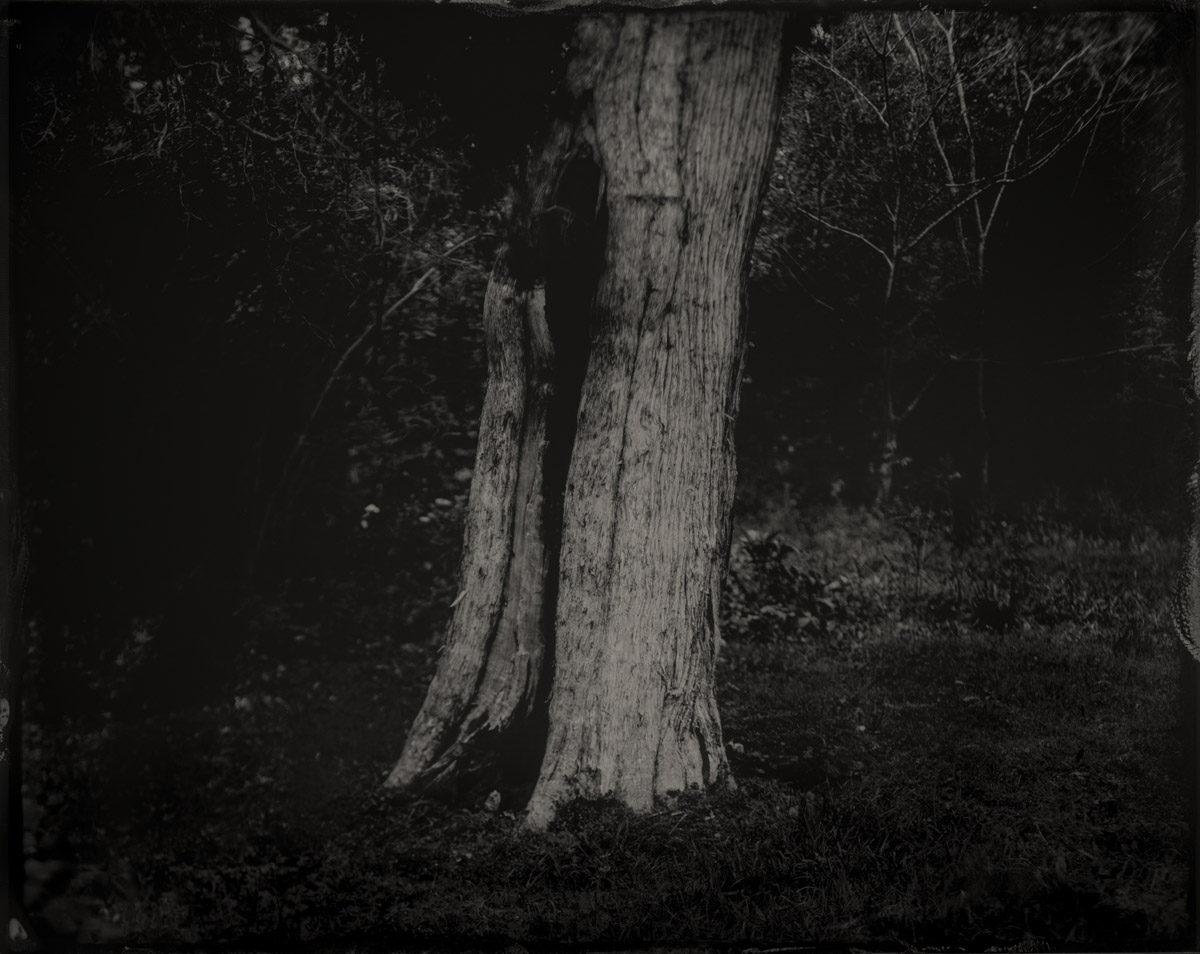

Hollowed cedar tree at the entrance of Manitou Cave, outside of Fort Payne, Alabama, formerly Willstown, a Chickamauga settlement of the Cherokee nation, 2017

Many Native American tribes attribute special spiritual significance to cedar tree, calling it the “Tree of Life” or “Holy Tree.” In particular, the Cherokee, who inhabited Manitou (an Ojibwa word meaning, “spirit”) and the surrounding area, believed that cedar trees held the spirits of deceased ancestors and therefore possessed the power of protection. Inside Manitou traces of human activity date back 10,000 years, including inscriptions from the Cherokee syllabary, invented by Sequoyah while he lived in Willstown. After the Cherokee removal on the Trail of Tears the cave was used as a Confederate encampment and saltpeter mine; in the 1920s it was converted into a tourist destination where flappers danced the Charleston in a “ballroom” that featured electric lights; and during the Cold War it was outfitted as a fallout shelter. After decades of neglect the cave is the focus of grassroots historical and environmental protection and in 2016 was listed by the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation as one of the state’s “places of peril.”

Site of Turkeytown, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017

Established some time prior to 1770, Turkeytown was one of the most important Cherokee cities in the region. Following his victory over the Muscogee Creek, General Andrew Jackson visited his Cherokee allies at Turkeytown in 1816 for a Council of the Cherokee, Creek, and Chickasaw to negotiate boundaries and ratify a peace treaty as Alabama opened to white settlers. At the council the Cherokee ceded a large portion of their ancestral lands in north-central Alabama to the US government and agreed to the building of roads throughout their domain, including construction of the Alabama Road over the ancient hunting and trading paths that once ran east to Rome, Georgia. Soon after the treaty the Eastern Woodland native Americans were forced west on the Trail of Tears.

Ohatchee, Calhoun County, Alabama, 2017

Near this spot a marker stands memorializing the place where General Andrew Jackson found and adopted an orphaned Muscogee Creek baby in November, 1813. The story recounts how the baby was found in his dead mother’s arms and Jackson had such compassion that he took the child and raised him as his own. What the marker does not report is that it was also near this location that Jackson’s Tennessee militia began their genocide of the Red Stick Muscogee Creek Confederacy. The day before Jackson found the child, his forces trapped hundreds of Muscogee men, women and children inside their log homes and burned them alive. In his memoirs, Tennessee Volunteer Davy Crocket wrote that the few Creek who escaped were “shot down like dogs.” The ultimate defeat of the Red Sticks during the Creek War led to the loss of 23 million acres of ancestral land. The final treaty was dictated by Jackson, who after the conflict would be promoted to Major General and later become president. His portrait currently hangs near the Resolute Desk in Donald Trump’s Oval Office.