London-based illustrator and cartoonist Tom Gauld probably doesn’t need an introduction. His work has appeared in outlets like The New Yorker, The Believer and The New York Times. He’s also been doing a weekly series of comics for The Guardian’s Saturday Review since 2005 — a collection of which became his second comic book, You’re All Just Jealous of My Jetpack (2013).

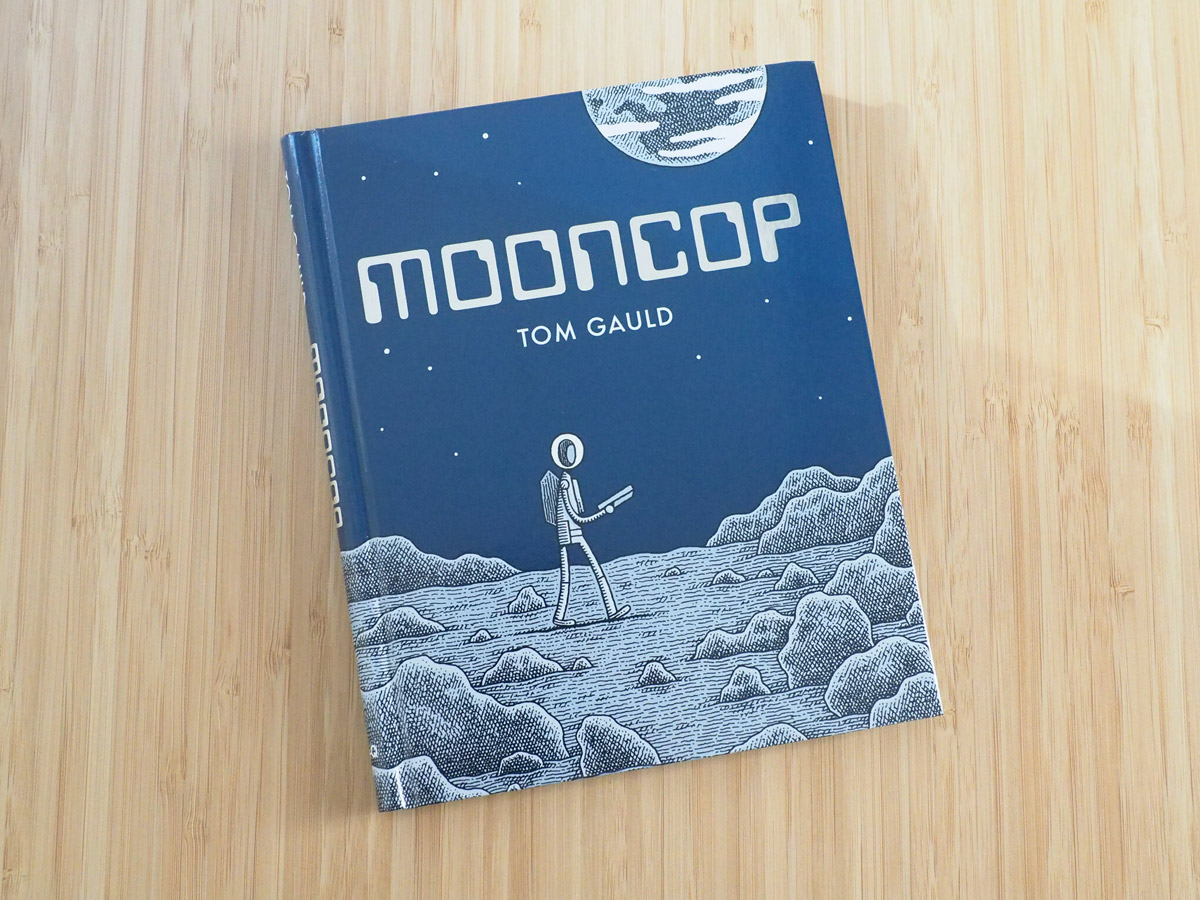

His latest masterpiece, Mooncop, is similar in tone to his first graphic novel, Goliath (2012) — a deadpan retelling of the Bible story. Set in a future where the idea of living on the moon isn’t just a possibility but a reality so passé that the one remaining policeman has little to do other than watch the last few colonists move back to Earth, Mooncop brilliantly side-steps obvious drama, focusing instead on things that are far more mundane and all too relatable.

Mooncop hits stores September 20th! Thanks to our friends over at Drawn & Quarterly, we have two copies to give away! They also put us in touch with Tom, who was kind enough to tell us a bit about his process, how he stays motivated and what had him laughing so hard he had to stop drawing! Check out the full interview below and share your favourite book or movie set in space in the comments for your chance to win!

Booooooom: We get a sense of the Mooncop’s daily routine very quickly. What’s your day-to-day like? Do you tend to follow a regular schedule?

Tom Gauld: I do have a routine. I work best in the mornings so I try to get to my studio by 8.30am and get started on some drawing. If I can, I work on creative things all morning and leave anything else till the afternoon. If I get stuck then I’ll take a walk and work in my sketchbook in a café for a while. A perfect day is making comics or illustrations all day, but more likely I’ll have to spend some of the afternoon on emails, orders or some other admin. In the evening I might make a few notes or sketches but I’m more likely to relax instead.

Comic for The Guardian’s Saturday Review

Booooooom: Do you approach things differently when you’re working on a weekly comic strip versus a longer project like a graphic novel?

Tom Gauld: They both start in the same way which is me sitting down with my sketchbook and making notes and doodles until something begins to take shape. For a short cartoon I’m generally quite quick, so I’ll spend maybe half of a day in the sketchbook then another half day drawing up the cartoon. Whereas with the longer projects I’ll spend a lot more time planning, making notes, researching and editing before getting to the actual drawing. The short, weekly deadlines for my Guardian and New Scientist cartoons force me to just get on with it, but with both my graphic novels I had periods where I got stuck. I also let a few people read and make suggestions for my longer stories in a rough format before I make the final drawings, however with the short cartoons I just rely on my own judgement.

Booooooom: When you were first starting out, was there a specific moment where you felt you’d finally settled into your own personal style? What helped you get to that point?

Tom Gauld: I think my work came together properly in the couple of years after I left college. I was making lots of illustration work to support myself and lots of comics because I loved doing them. Making lots of work knocked my style into shape, simplified it and improved my storytelling. With hindsight I can see that the style had been developing in my work from my first (awful) teenage comics through the stuff I was doing at college, but the development was obscured at the time by various experiments, dead ends and confusions. I hope to push my work as time goes on, not to ‘find a new style’ but to improve what I’m doing and use it to do new things.

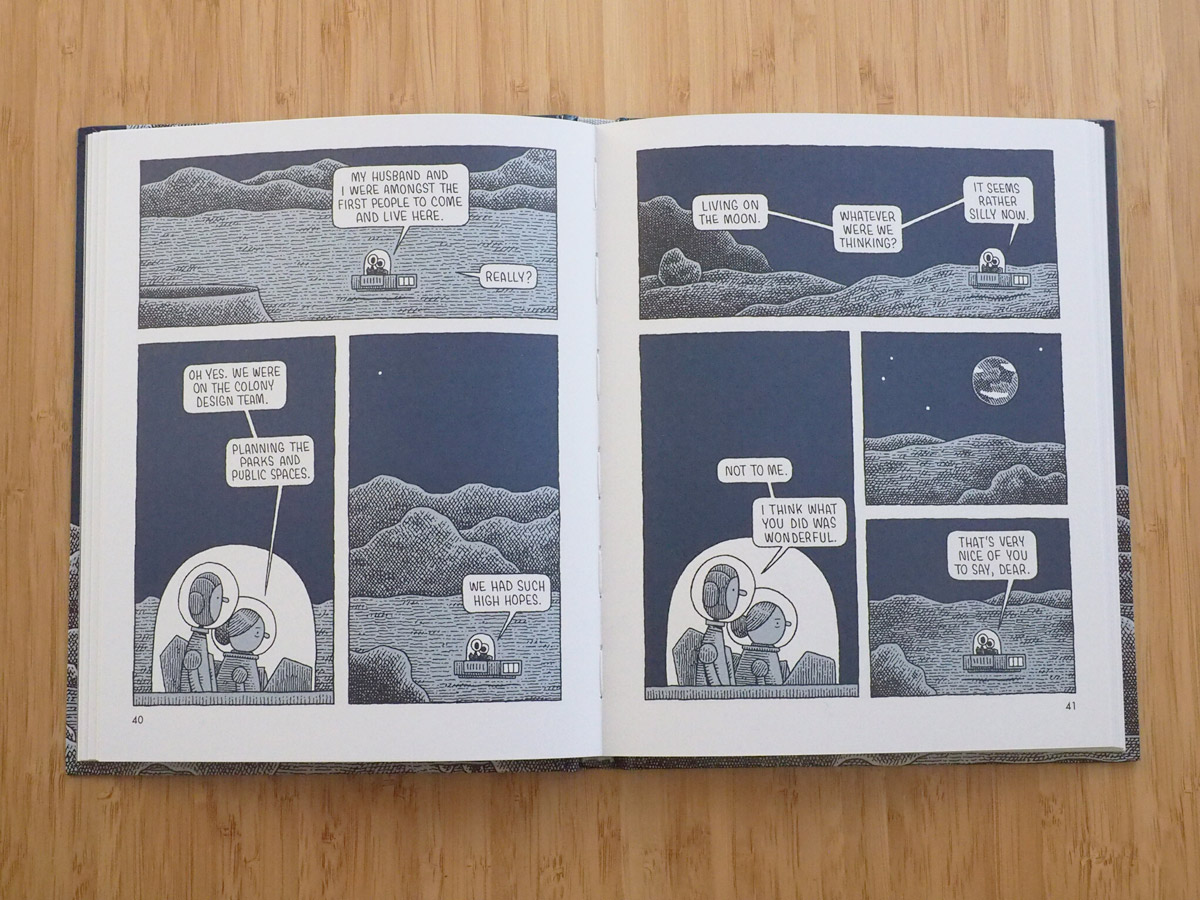

Booooooom: There’s a wonderful sense of quiet failure to Mooncop. The way you’ve set things up it’s clear that colonizing the moon was a large-scale project that’s coming to a close, not because of some huge miscalculation, but something more like a gradual loss of interest. Can you talk a bit about that idea? Did it come from anywhere specific?

Tom Gauld: It came from two places really. The first inspiration is the change in attitudes towards the moon, from the white-hot excitement of the space race, when people seemed to be seriously talking about a moon colony, to now, when nobody has set foot there for forty years. It seems that in the sixties there was a simple wonder about science and technology and their ability to make our world better which has gradually dissipated. Not that there’s none of that belief today, but its more nuanced and debated. As a child in the very early eighties I remember taking a (supposedly) non-fiction book out of the library which suggested we’d be holidaying on the moon by 2010.

The second inspiration is the optimistic, almost utopian, modern architecture of the sixties and seventies. Especially the big concrete constructions built to house ordinary people. They were made with such high hopes of making new, exciting homes and cities which would improve people’s lives and take us into a high-tech future. I think many are lovely, but, in general, they aren’t much loved today and many are dirty, crumbling or have been knocked down.

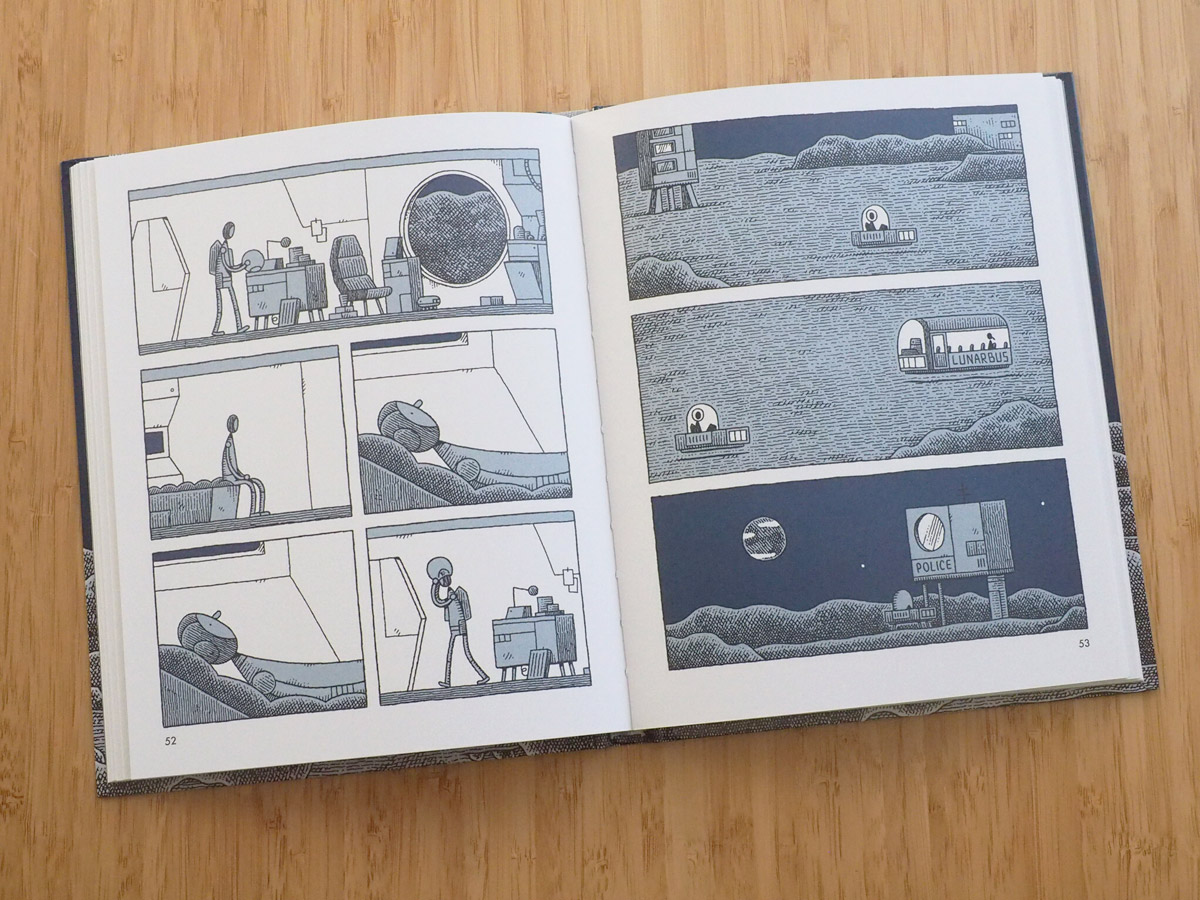

Booooooom: You have a great knack for pacing. When planning out your panels on the page, do you just instinctually know how things should go or is it something you’ve had to work at perfecting?

Tom Gauld: Thank you! Using the panels and pages of a comic to break down time and tell a story is for me one of the most interesting parts of making a comic. Just one extra panel in a sequence can give a pause, a moment for the reader to reflect, or put something of themselves into the moment, and this can make a big difference to the elements before and after it. Comics are made up of words and pictures, but the real magic comes from the third element which is how they interact with each other on the page.

I use a funny mixture of instinct, careful planning and trial and error. I make lots and lots of little pencil thumbnail drawings of the pages with tiny panels to work out the pacing and I keep editing and changing the page layouts as I go along.

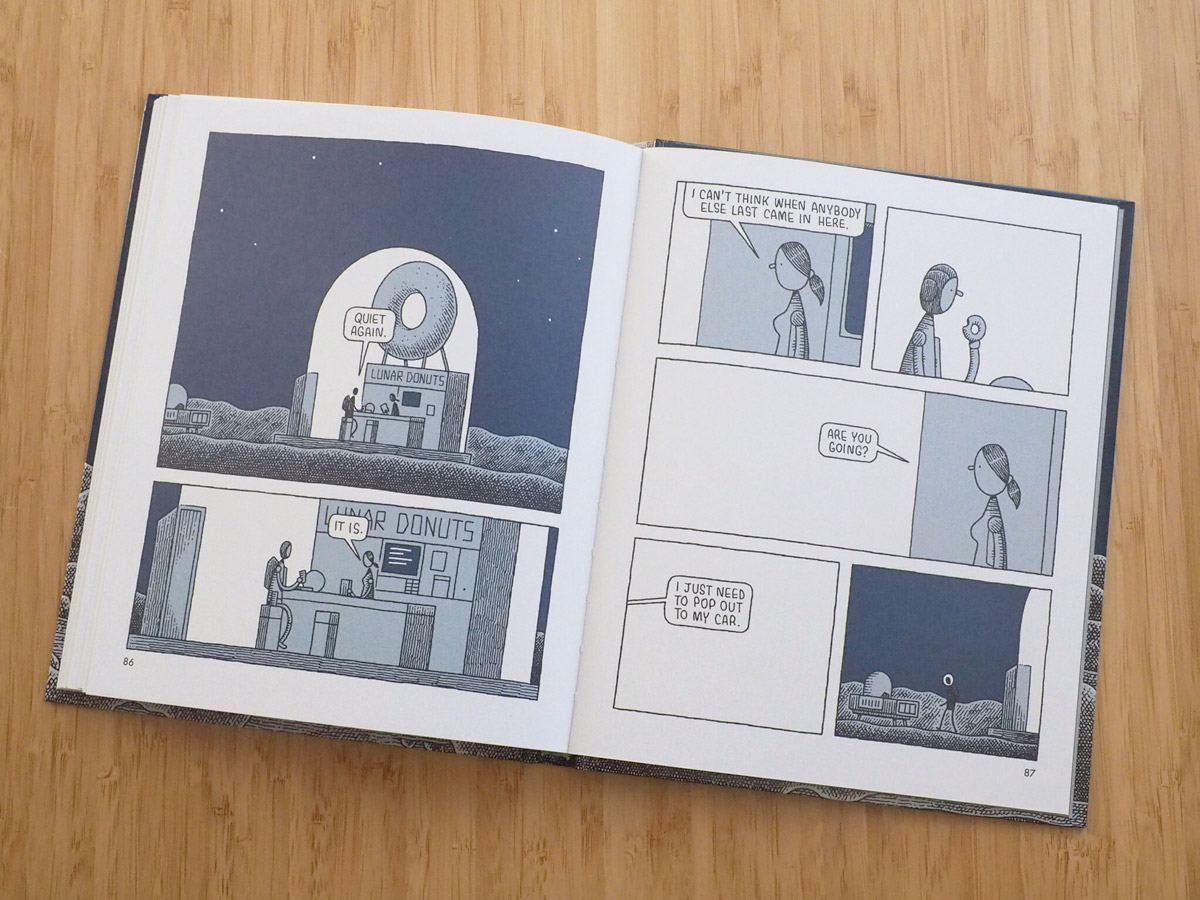

Booooooom: “Melancholy” seems to come up a lot in the early buzz around Mooncop. Do you think that’s fitting? If you had to choose one word to describe the book, what would it be?

Tom Gauld: Yes, it does come up and I do think it’s fitting, although it could suggest a humourlessness which would be misleading. People sometimes say the work is ‘deadpan’ and I think that’s true. It’s very hard to come up with a single word, perhaps there is one of those long, German compound-words which means both melancholy and funny.

Booooooom: How do you stay motivated when working on a longer project (or just working creatively in general)?

Tom Gauld: I think with a longer project that staying motivated and just ploughing on with it are probably more than half the battle. My main trick is to force myself to do a little work on it every day, in the hope that on some (or hopefully, many) of those days, things go well and I keep going and get lots done. It doesn’t always work and the world is full of distractions.

Booooooom: Are there any sources of inspiration that people might not expect you to be into?

Tom Gauld: I have big books on Stanley Kubrick and Pieter Bruegel the Elder which I often flick through for inspiration. I think it’s the almost obsessively detailed worlds which they’ve created that appeals to me.

Because I plan my comics so carefully, inking the final pages can get a bit repetitive so I listen to audiobooks and podcasts. I love Jon Ronson’s audiobooks and the BBC podcasts Free Thinking, In Our Time and More or Less.

Booooooom: Your work operates within a specific sense of humour, somewhat dry and more subtle than an overt gag. What makes you laugh really hard?

Tom Gauld: I find the comedy television and radio programmes made by Armando lannucci very funny. He’s probably best known for making Veep in the US, but all his stuff is brilliant. I was listening to the audiobook I, Partridge (which he co-wrote) while I was finishing Mooncop pages and had to stop drawing because I was laughing so hard.